It’s no coincidence that ArtJaws has chosen to dedicate its first digital art collection to the body, which has long been neglected by this art medium in favor of abstract forms. In the past few years, however, the body has figured more regularly in digital arts. The interaction between the imagination and technological tools, mutually inspiring, finds in the body not just inspiration, but incitation—as if exploring all the possibilities of the body, seeing how far it can go in representation. From this point of view, digital art extends and renews the research begun long ago in the traditional arts.

For example, some artworks test the sensual body’s resistance to the skin’s transparency, as in France Cadet’s Anatomy Lesson n°32, or mix genres in Anatomy Lesson n°47, which fuses advertising pose, piercings, anatomically correct mannequin organs and self-demonstration of those skinned raw by the Renaissance, with a transparency that is demanded by our time, as our contemporary obsession.

These are the digitally augmented bodies. If in many cases, traditional photography already offered the same possibilities for manipulating images, in digital media, the superfine definition and grainless homogeneity of images makes imaginary worlds appear unbelievably realistic. We know that in digital media, there is no present, no here and now as witnessed by photography, but instead the image itself powerfully manifests a “could be” similar to René Daumal’s Mount Analogue: “I felt that deep down, despite it all, something in me firmly believed in the material reality of Mount Analogue…” “I mean to say that it could very well, theoretically, exist in the middle of this table…”

Urban populations could cross a desert and mountainous landscape, or a forest, or a seaside (Jean-Pierre Attal, Ethnographical Landscape n°10, 14, 13). It’s not so much that we believe in the situation of these displaced bodies—in the sense that they are out of place—but that the “dichotomy between characters and landscapes” acquires a strong visual credibility within the image. It is even reinforced by the pixelized faces, confirming the digital nature of the image, while suggesting a concern for each individual’s privacy, as if this situation referred to the reality of a current affair. Such is the ambiguity that is characteristic of digital art.

This same ambiguity reigns in Reynald Drouhin’s interpretation of Gustave Courbet’s The Origin of the World (1866), as the pictorial gesture is replaced, upon closer examination, by a multitude of autonomous images lifted off the Internet. In this way, the Portrait of Louis-François Bertin, painted by Ingres in 1832, i.e. before The Origin of the World, contributes to representing the model’s pubic hair, along with Paul Gauguin’s self-portrait painted in 1893. As the images are collected at a very specific moment, while everything is constantly changing on the Web, the portrait of Joanna Hiffernan also becomes a portrait of the Internet via a collective. As the origin of the world moves, is the Internet not a sort of great matrix?

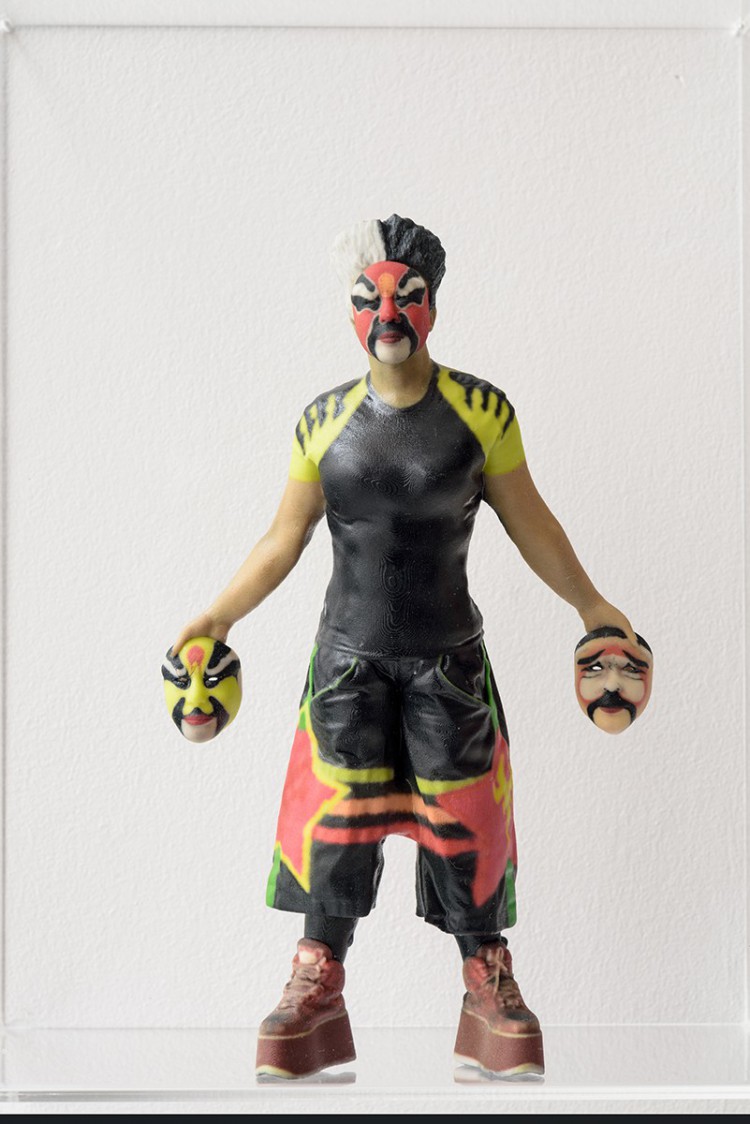

Digital media is one of the new molds (matrix) of art forms. ORLAN’s Queen of masks / Peking Opera, Facing Designs and Augmented Reality is a sculpture printed from a digital file. The artist’s virtual avatar, entirely conceived inside a computer, joins the world of objects, and despite its small scale, the sculpture inhabits our space with its strong presence—gathering forces by concentrating them. Meanwhile, Catherine Ikam and Louis Fléri atomize the face into a cloud of a million dots (Portrait Particules 1 and 2), using 3D scanners and dedicated software to deconstruct and reconstruct it. This face becomes a constellation, an expanding and contracting universe, a metaphor for the human psyche, alternately open and closed, for its instability and the multiplicities that make up individuality.

Maurice Benayoun’s Dildomatic Opera addresses the individual, he or she who will use his or her sex toy to produce interesting sounds. This double interaction involves doing things with the object, while communicating to the audience the sensations felt and converted into sounds. If the work is playful and humorous, with its highly polished luxury case, for the artist it’s also a metaphor for art as “a form of onanism, narcisstic and desperate”, all the while being part of the interaction. Thus, another metaphor is juxtaposed with the first, as the artist explains so well: the interaction is the dialogue of which the extreme forms are “make love” and “make war”. By choosing love, the body and its sensuality, Benayoun sweeps aways a cliché of digital art that is not necessarily disembodied. On the contrary, digital tools are amplifiers, they can increase our perceptions and multiply our means of expression, including corporal.

Albertine Meunier’s Angelino is precisely an amplifier of perception, signaling the passage of angels on Twitter by triggering the movement of a music box dancer. With its poetic interpretation of time, counted in passing angels, the artwork literally connects a decorative object from the late 18th century to today’s open source technology (Arduino).

In this supposedly eclectic collection, which reflects the diversity of practices related to digital art, we still find, among others: living genealogy written inside a skull (Pia Myrvold, The Million Year Memory, I and II); Imaginary Encounters with ourselves in Scénocosme’s installation; eroticism à la Georges Bataille with a nod to Lucio Fontana’s slashes in Magali Daniaux and Cédric Pigot’s Fontanaeyes; Christophe Luxereau’s luxury chic vanities in a spectrum associating color and matter—shell red, marble white, gold yellow, porcelain blue, crocodile black, jade green. Digital media, the new matrix of art, like a blown-up studio, networked or not, amplifier of our senses and means of expression, with the ambiguity of a “could be”, augments bodies with its potential, defying our imagination.